This is another in a series of writings that attempts to explore a social phenomenon that may have a profound impact on the self-development and personal growth of individuals involved. Similarly, it may have an equally profound effect on the overall morality of a society.

If the rules of formal institutions and even cultures (defined generally as conventions we feel compelled to follow, ranging from formal laws to cultural mandates) are reliable for their inviolability (often framed in moralistic terms of certainty of rightness, therefore violators deserve punishment), and so must be followed as unassailable matters of form, why does there seem to be substantial justifiable flexibility when occasions seem to warrant (Church, Navy, government, etc.). It would appear that rule inflexibility normally appears to benefit authority, whose self-interest is best served by compliance as a means of promoting a social order that erases many of the burdens of governing—and of being reelected. Rule followers, or those who are expected to follow the rules, on the other hand find their options limited by inflexibility. It is not difficult to visualize the concept of rules as 1) a restrictive control device to keep the powerless in that state and 2) a flexible construct for the powerful which enables them to promise discipline, or punishment, for the powerless while retaining the ability to improve their own circumstances and position. At its worst, rules (most often in the form of conventions or cultural norms) in a participatory society tend to be used by authority to exercise control in informal, even illegitimate, ways that cannot be imposed legitimately.

In order for authority figures to effectively impose rule-following conventions, a population must be amenable. And they are most likely made amenable either through conditioning or coercion. Their early lives may be filled with specific instruction and direction that tend to make them dependent on rules for their security (the corollary, of course, is that by receiving consistent and specific instruction one does not develop the capacity to think, or solve problems, for oneself, hence I am dependent on another). Coercion, of course, occurs when one is, usually, physically forced to follow the rules. Conditioning has the added promise of making plausible the need to follow rules in order to earn security.

One typical-to-an-extreme example may be a former CIA officer who, when asked “You ever kill anybody?” said “I've made decisions that resulted in people's deaths, maybe hundreds of people's deaths, but I never lost a night's sleep. Never. Because I had 500 pages of U.S. law to hide behind.(p. 135)” (Tyrangiel, Josh, “So, you ever kill anybody?”, Time, November 21, 2005, pp. 132-135)

This response suggests some sense of right-and-wrong (which one would hope to be present in cases of life and death), but an overriding willingness to “hide behind” authorities (the laws, in this case) in engaging in the larger wrong of sacrificing lives. It is particularly important that this excuse be available when the deaths may not otherwise be demonstrated to pose a specific, immediate and catastrophic danger to the sponsoring state. Presumably a principles-and-reason person would cite the greater good that would result from his decisions, supported by law, to kill. The reasoning options also illustrate the premise that it is most often not the moral decision one makes but the reasoning behind it that determines one's moral dimension. A decision supported by precedent may appear the same but be very different from a decision arrived at through application of principles and reason. Lawrence Kohlberg pointed out that the rules-oriented person finds it virtually impossible to understand a decision reached through reasoning, attributing it to the decision maker rationalizing his way into a self-serving favorable decision.

A basic premise behind demands for obedience is that rules are based on absolutes and therefore not subject to review, discussion or violation without penalty. The absolutist disseminating (or feeling compelled to obey) these rules expresses contempt for the “relativist” who seems to make decisions based on self-interest. A virtue of absolutism is the minimal concern of immediate selfishness or self interest since the actor is following external direction to avoid punishment or penalties. This suggests, perhaps erroneously, that the actor is concerned about others, when in fact the concern is for self and the avoidance of punishment or sanctions.

Much is made by the so-called Creationists of literal interpretation of the Bible, and, in a political context, a literal interpretation of the Constitution. Both are relative to the intentions of the creators (God on the one hand and the Founding Fathers on the other). Only a very few thoughtful people (I hope) cling to the notion that the earth and all on it were created in seven 24-hour days, literally. While it may be that such an occurrence did happen, the knowledge that God has allowed discoveries, over the past 2,000 years that strongly support the notion that the earth is far more than 4,400 years old. Creationists are captives of literal interpretation and find it difficult to be figurative, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Beyond that, of course, is their insistence that literal interpretation be followed to the extent that schools, their districts, etc., are pressured to teach Intelligent Design (the non-religious equivalent of Creationism) as a scientific theory alongside evolution. Inclusion of such teaching reduces the threat of pluralism they perceive (in the final analysis) as being unhealthy for their children.

A byproduct of the creationism environment is the expectation that emerges when one is a literalist. There is likely to be a sense that the divine, in whom they have genuine faith, has given them a “precise, revealed blueprint for political life, which means that for the foreseeable future they will not enter into the family of liberal, democratic nations.” (Lilla, Mark, “Godless Europe,” a review of “Earthly Powers: The clash of religion and politics in Europe from the French Revolution to the Great War [Harper-Collins, 2006] in the New York Times Book Review, April 2, 2006, pp. 14-15).

The reference is to Islam in the context of today's climate and efforts at nation-building, but it might also refer to Fundamentalist Christians in the United States and other countries whose sense of “blueprint” appears to differ only in a matter of degree from that of Muslims: “Even in the United States, we are witnessing the instrumentalization of religion by those who evidently care less about our souls, or even their own, than about reversing the flow of American history since the 'apocalypse' of the 60s.” (Lilla, 2006, p. 15)

The reference to the family of liberal democracies is important, since the U.S. Is specifically viewed as a liberal democracy, a society in which change (read that progress) routinely occurs. This contrasts drastically with the traditional cultures in which fundamentalist religions are entrenched and in which change is vigorously resisted.

Arguably, the change orientation of a liberal democracy is responsible for its membership in the advanced ranks of nations, in terms of many important objective measures—low infant mortality, high education level, high literacy, greater political participation, life expectancy, etc.

Strict constitutional constructionists, consisting of many of the same people as the creationists, are conservatives who seek to limit lawmaking and interpreting to the intentions of the Founding Fathers who drafted the U.S. Constitution. They allow no leeway for the courts to interpret according to changing conditions, new discoveries, social developments, etc. In a further step, they see court rulings that are progressively interpretive of the constitution, and subsequent law, as “making law” in violation and contravention of the constitution.

A hidden hallmark of both groups is their resistance to change; rules tend to assure a status quo with no threat of change.

If the Creationists, Christian religious fundamentalists, believe that Genesis (which contains the most complete account of the creation) must be taken literally, they have no leeway in interpreting other parts of the Bible and must be captives of literal interpretations, even from the New Testament when Jesus uses parables to teach—the ox in the mire in relation to Sabbath observances, the Good Samaritan in relation to doing good for neighbors and those who are despised, etc. In this event, there is little ability to adapt to current conditions in which few oxen are to be found literally in the mire and fewer battered despised lying by the roadside in this day and age. The Christian principle behind the parable of the Good Samaritan, of course, is one of helping those in need, a general mandate not limited to roadside casualties.

Even the Catholic Church, which asserts itself as having unchangeable dogma while masking changes (resisting the appearance of change, even changes are introduced by “As the Church has always done it . . .”). John Noonan in his “A Church that Can and Cannot Change” notes four significant changes (“Adaptation to new knowledge or circumstances”) in the past two centuries in Catholic dogma. They are in the areas of slavery, usury, religious freedom and marriage. More minor changes, such as meat on Friday, language of the mass, etc., have also occurred in “unchanging” Catholic doctrines and principles.

A reviewer said “Noonan believes in an unchanging element in Catholic teaching, a core continuity from Jesus to today. But from his cases he can deduce no rules of thumb to determine what falls within this continuity.” (Steinfels, Peter, “Dogma,” The New York Times Book Review, May 22, 2005, p. 26.

This may be a valid summary for the thinking of other principles-and-reasoning proponents in the face of the absolutist.

The statement above is very significant in calling attention to the “absolute” virtues often invoked, but recognizing that little is done to validate their absoluteness, making it difficult to pin down what may, indeed, be absolute. Ultimately, such absolutes become acceptable as Truth on their face and by tradition. They also are conveniently used as landmarks guiding the timid through the shoals and rapids of life.

Many who declare the need for obedience to commandments tend not to identify the commandments being referred to. Instead, the admonition to obedience seems to be all inclusive, extending to many rules that may or may not be commandments, but which it is convenient for followers of the invokers to be required to obey. Such sweeping mandates also have the practical effect (in their consistency and precision) of creating the important habit of obedience in which invocation of the admonition to be obedient triggers a visceral reaction to obey.

Much is made of the importance of absolutes (or the “core continuity” noted above) as bringing some reliable order into a chaotic world. A key question is, what are absolutes? Love thy neighbor seems to be a good absolute, as a general instruction. When it comes to specifics, however, some neighbors appear not to warrant love when they act in despicable ways toward either us or, most especially, toward others. It is not that we may be seeking to punish others for their despicable ways, but that we may offend or harm others (unnecessarily and harmful in its own way?) in protecting ourselves from harm to us resulting from those despicable practices. Polar examples are that we refuse to let our children associate with other children whose behavior we see as being harmful to others (either physically or spiritually), thus offending those children and their families; and in some cases doing serious harm to their social development and/or social acceptability. Or, of course, we may do physical harm in self defense to one who is attempting to harm us.

Similarly, neglectful parents may not be worthy of the love of their children (though some church leaders do talk of the obligation to love parents unconditionally). And certainly few of us believe the admonition that thou shall not kill. Exceptions are readily made in times of war, or when a person is threatened, or in the case of the execution of one who has killed in cold blood, etc. Virtually all the commandments are acceptable in general terms but require interpretation, and in some cases perhaps outright rejection in the specific. It may be desirable to state that I must love the sinner while hating his/her actions. However, if the sinner is to be punished (questionably acceptable in New Testament history), it must be the obligatorily lovable physical presence upon which punishment is visited, often making it difficult to determine how to separate the individual from the transgression. Punishment from love seems often to have a hollow ring (destroying a village to save it, a relic of Viet Nam, comes to mind).

And, see section #9 below, we do nothing more than pay lip service to the requirement that we not bear false witness. For all our interest in seeking truth, and believing we should dispense nothing but truth, we routinely demonstrate there are many exceptions to the rule.

Indeed, the strong marketing philosophy of the LDS Church (a missionary, therefore marketing, church) is based on dispensing its truth to the exclusion of truths and facts which do not support the marketing/missionary efforts. This is not necessarily bad. In fact, it is a manifestation of a universal and widely accepted marketing practice. However, it should not be masked as a “telling of truth” if the sin of omission is, indeed, a form of lying. The point here is that we demonstrably have less of a commitment to the sanctity of truth than we do to the advancing of our particular, and self-interested, views.

What is truth? The dictionary definition, of course, tells us it is what is. An operational definition for our discussion of marketing/missionary is that truth is what whoever we are working with will encounter as a result of our efforts, and it is a critical moral question. That is, the image we build in the mind of our subject should be based on the moral imperative to match what we, in serious good faith, believe the target of our efforts will encounter. The marketer works in images and those images should match the reality. To the extent the image and the reality differ, the ethics of the image maker is at fault.

Truth is very awkward as a social device. And our reluctance to tell the whole truth in marketing efforts emphasizes the problem; most of us would not want to live in a world where absolute and full truth is told routinely. It would be awkward and disruptive of social and personal relationships, at the very minimum. All of which is not to trash the concept of selective truth in marketing or missionary work, but to dramatically illustrate the point that absolutes are well nigh impossible to identify; and to suggest it is fatuous to believe there are recognizable absolutes by which me must live. Specific behavior defies absolutism, but the value of principles is great in providing direction to all decision makers, particularly to absolutists.

Louis Pojman, a philosophy professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, said it is his experience that the only absolute he can certify is one that prohibits one from doing unnecessary harm to another. This is akin to the notion, above, that there probably are absolutes but mere mortals, with all the advice available to them, apparently have a difficult time determining what they are and must settle for one or two abstractions. It might even be presumptive of humans, given their limited knowledge, to confidently list absolutes that bind the human condition.

It must be recognized that if, indeed, it is absolute, under the laws of nature or of God, that we must love our neighbor, and honor our parents, or not kill, and that we must unsparingly tell the truth in all instances, then we will inevitably and demonstrably have, in a contrary way, made the decision as individuals and as society that there are exceptions, and we will be wrong, perhaps grievously wrong, one way or another. Either we are hypocritical in pretending to be absolutists while acting otherwise, or we will knowingly and openly break the absolute commandments and will presumably pay the penalty either here or in the hereafter. It is not enough to say that we believe in absolutes but that human weaknesses account for departures from the absolute, since we have institutionalized those violations of absolutes and seem to routinely and knowingly violate them.

Perhaps the only absolutes we can have confidence in, based on absence of specific knowledge, is the absoluteness of the need for us to fulfill certain ordinance requirements: baptism, priesthood ordination, sealings, marriage, etc., though these also are performed by proxy when not done in our earthly form.

The institutionalizing of absolutist notions, of course, smacks of gross cultural hypocrisy but is seldom acknowledged, and almost never discussed publicly. Perhaps the masking is indeed done out of consideration for us, so that we as individuals are not required, by and large, to recognize hypocrisies to each other.

In any case we are left to our own individual and societal devices in determining whether rules/laws/etc. are absolute, and this requires reasoning power. Most of even the most avid rule followers reserve for themselves the right to make decisions on how absolutely the more commonly violated rules must be interpreted and obeyed.

In that mix we introduce the type of an individual who needs the security of stability and that guiding hand of ostensibly absolute instructions, and the type who assumes the principles are there, though they are sometimes called absolutes, and decisions must be made from among competing principles.

There may be an interesting difference between the need to seek power that differentiates rule followers from the relativists. Rule followers need to have compliance by others if rules are to be effective. The relativists, those a little more relaxed about the rules, tend to seek power in order to free themselves from the restrictions imposed by rules.

Rule followers acquire power in order to install social mechanisms that will assure that subsequent generations will tend to, by and large, follow rules (even supporting those which violate one or the other of “absolute” commandments) and contribute to social order. And, as power is accumulated by those who make and enforce the rules, there is a tendency to create more rules that will allow a greater centralization and accumulation of power. In step with the creation of rules is the expansion of punishment, or promises of punishment, for violations.

Compelling conventions are, in part, the everyday habits we have had thrust upon us with which we comply without question, or without periodic evaluation for their validity in the face of changing times and conditions. This involves such every day behaviors as regular eating and sleeping habits (certain foods are acceptable for breakfast, eight hours a night between prescribed hours, etc.), and may extend to such things as avoidance of conflict, suspicion of innovation, etc., which are unconsciously accepted as appropriate and which feed our decisions as a matter of course.

One conventional wisdom which may have outgrown its usefulness in the modern world, but which is still embedded as a virtue which must be taught to the young, is the virtue of developing physical work (hard work, etc.) habits. Many adults tend to decry the absence of physical labor opportunities for young people which would help them develop the lifelong habit of regular physical labor—presumably a character-shaping behavior. One neighbor, with a strong belief in this behavior, borne of hard work on a farm/ranch in his youth, found a plot of ground in the neighborhood to plant in a garden in the summer, largely so his growing children would have an opportunity to develop the physical work ethic and discipline required in the tending of the garden.

Another father complained recently to me that the youth of today are too soft: “They just aren’t tough.” He recalled whippings by his father when he was young and decried the absence of capital punishment today. He had his boys play football, do hard physical labor and engage in other toughening up activities. Still he was puzzled that two of his sons had completely gone off the track he intended for them. They were into drugs, alcohol, etc. Further, he despaired of ever healing the breach between father and sons. He did not make, verbally at least, a connection between his ideas about child raising and his sons’ behavior.

My argument against the physical labor philosophy, though such a philosophy may still be valid to some degree, is that the world has moved away from physical labor and toward the necessity of engaging and developing the mind in order to succeed. That is, there is an increasing probability that it will better serve a young person to develop the mind (as well as self-discipline) and to be able to think critically and reason, and solve abstract problems in the modern environment, than to develop physical working habits. Indeed, at an extreme of the argument, it is better for an individual to be able to reason through to a better solution to a problem (even with laziness as a stimulus to avoiding physical labor) in ways that are quicker and involve less physical involvement than it is for the individual to habitually work through the physical solution in a world increasingly moving away from work requiring such involvement. While on the one hand this may be viewed as an exhibition of laziness and sloth, on the other hand, serious thought leads to innovation, something the hard physical labor school neither account for nor encourages.

Thus, the compelling conventional wisdom of “labor by the seat of thy brow all the days of thy life” actually tends to work against necessary mental development needed in today’s world, creating victims of those who do not think through the implications of this particular conventional wisdom.

Perhaps one of the most pervasive and enslaving of compelling conventions emerges in our relationships with others in which we attempt to provide answers the questioner expects, rather than responding as our true feelings would dictate. This convention tends to stunt individual development and denies the individual the right and ability to develop an original personality. Instead, it produces a personality to fit the expectations of the surroundings.

“Rules” in this context may range from the formal laws and ordinances that govern societies, and tend to protect each from the other, to the informal conventions or social traditions that compel us to act in certain ways. In traditional cultures, in particular, such conventions have a powerful hold on its members and become so binding that severe sanctions are imposed on those who violate them. These conventions may include deference toward elders, avoidance of conflict or controversy, resistance to innovation, privacy expectations, slavish following of precedent, and others.

Do rule followers (those conditioned to follow the rules—a leader’s paradise) have a legitimate right to explore rules for their flexible characteristics? Peripheral: Does emphasis on obedience in the Church benefit leaders (as a class), or the Lord’s plan, or both? How does one become a God by following rules (albeit informal) which appear to tend to be a severe inhibitor of one’s development to that end? It is the same problem created by “in order to be free you must accept restrictions (or, “you cannot have freedom without being responsible”).” This phrase, often offered without explanation or discussion, strikes me as simplistic, and even stupid. As in so many other things, it needs discussion for its shadings, exceptions, and clarifications. It is through discussion that the powerless individual gains the tools that lead to power over his/her own destiny by being able to make informed, reasoned decisions rather than being a prisoner of injected responses.

Seldom are rules made that free one to act. By and large, rules tend to be restrictive. Hence, whatever their validity, they reduce the agency of the individual and ultimately sap the creative will as rules become more pervasive in one’s life. Not that reduction of agency is invariably a negative, but the fact is that agency is reduced. Inexcusable destruction of someone’s agency is, however, a negative.

The Bill of Rights (the first 10 amendments to the Constitution of the United States) seems to be an exception, however, and its provisions are remarkable for NOT restricting individuals. These amendments generally prohibit restrictions on individuals—thereby creating an individualistic society in which humans should be valued and allowed a maximum of liberty and individual agency—and have generally been durable. Another proposed amendment, however, would reduce liberty of individuals (whether rightly or wrongly) by restricting the right of individuals to treat the American flag as they would.

It should be noted that extreme individualism produces chaos and is healthy neither to society nor to the individual. Society would find it difficult to marshal cooperative efforts in necessary areas and the individual finds that society is harsh with those who blatantly disregard the more basic conventional wisdoms.

It also seems to be axiomatic that as a rule maker sees the hold rules have on followers, with the inevitable power that comes from controlling others, the rule maker sees the great benefits of accumulating more power by making and disseminating more rules that restrict (or control or bring order, or whatever) the rule follower while vesting the rule maker with more power. It must be recognized that the rule maker may feel and altruism in bestowing benefits on the subject or actor by imposing rules; yet each rule constitutes a denial of free agency to some greater or lesser degree. Hence the scripture, “Give a man a little power, as he will immediately begin exercising unrighteous dominion” and its corollary that others are to be led by the exercise of patience and long suffering.

Is the practice of, or tendency toward, rule following inherited, or is it the product of conditioned learning? If inherited, it certainly seems to disprove the notion that people have an inherent desire for freedom (or, perhaps more importantly, free agency). It would appear the inherited desire is more for security (a promised product of rule following) than for agency. If learned, it would appear that security is the primary concern and that the conditioning is relatively easy to accept for those who have an inherent (or learned?) need for security. If rule following is a learned trait, wouldn’t greater education tend to increase feelings of self-confidence and reduce the need for security, displaying itself as a willingness to take risks in life.

Children tend to be ready subjects for conditioning. It has become a primary purpose of elementary education to socialize children, another term for conditioning them to accept and conform to social mores. Whereas the three R's (reading, writing and 'rithmatic) were the traditional goal of elementary education, parents now may fear a broad, public education for the values it instills; particularly values that may conflict with parental values. As a society becomes more diverse, the clash of values becomes more likely. It then is a question of whether those clashing values are important to a child's education (and therefore must be countered or accounted for in the home), or whether education is the process of instilling non-controversial values. It would seem the latter would virtually guarantee that a child would not encounter diverse ideas, and would therefore have no need to develop mechanisms for dealing with diversity in his/her life.

In either case, it would appear that certain personality types seem to need the greater security that comes from acceptance by peers, thus contributing to rule-following incentives. Most studies suggest that some two-thirds or more of adults tend to need to be rule followers (a condition that yields personal free agency for the convenience of avoiding the exertions of reasoning one’s way to a decision). See section below for some reflections on whether such inborne dependence is inherent or created (conditioned). It probably is a combination of both, in which case the individual may have an increased responsibility to self to develop a sense of independence by overcoming both natural tendencies and the bombardment of conditioning from school, parents, church, etc.

It may well be that obedience to commandments is a primary divine command, but its implementation very often resembles power consolidation by leaders who find that compliant followers create fewer problems and leadership crises than do those who seek options to the views of power holders. Thoughtless, or even faulty, exhortations to obedience then may become control devices for the convenience of leaders. Further, of course, is the extension of authority and of the definition of commandment that may spread the concept wider than the Lord intended, or is intended in Gospel discussions. Certainly, obedience to commandments (of which there are relatively few) is a logical requirement. However, when virtually all words uttered by Authority (whether spiritual or secular) take on the protective coloration of Commandment, it begins to appear suspiciously like usurpation of the Lord’s authority and the utilization of the term for self serving purposes. What Commandments are there (beyond the original 10, or the 13 Articles of Faith, which tend to be much more general)? Concepts in the Word of Wisdom from the Doctrine and Covenants are said to have the power of commandment (though they also are quite general and have needed substantial interpretation over the years in adapting themselves to discoveries and new conditions).

The argument must be made, however, that the Old Testament is clearly a text that calls for rule-following, while the New Testament, which contains the foundation of the new Gospel of Jesus Christ, places more responsibility on individuals to govern their own actions by gathering information and reasoning toward a decision. The results of 2,000 years may be seen in the contrast between Jews (who reject the New Testament in favor of the Old) and Christians, with their often contradictory acceptance of both books. Jewish religion tends toward the strict interpretation of the Old Testament, resulting in what appears to the observer to be archaic behavior. Some Christians tend to be much more flexible (to the frustration of strict interpretation advocates), perhaps taking their cue from the story of the Ox in the mire on the Sabbath. However, it should be noted that many Christians do act as though the Old Testament holds primacy in times in which Old and New tend to conflict. I suspect this is a reflection of the need to be dependent, thus rigid rules tend to satisfy that need. Or, it may be a manifestation of conditioning to obey without question. It may also rise from a Hobbesian view that doubts the abilities of individuals to govern their own lives. Hence, the rule maker tends to offer assurances of security (either in he here or the hereafter) in return for obedience.

Hobbes differs from Kant on this in that Hobbes sees a “protective” rule making device for those who cannot govern themselves, therefore need rules to follow. Kant sees a rational human but expects individuals to reason for themselves and, once they reach a conclusion in a category, to be bound by their decision, an imperative. Once one decides to tell the truth, for example, one is bound to be truthful in virtually all categories thereafter.

Hobbesian rules tend to come from outside the individual and are accepted as part of a contract in exchange for security. Kantian imperatives come from inside the individual, but tend to be equally as binding in order to reduce the role of emotion in decisions. Kantian rules are made at leisure and without the pressures that accompany decision making situations.

Not surprisingly, virtually all leaders engage in the practice of advancing their views as commandment (which in its widespread incarnation just among secular leaders leads to suspicions of the motives of spiritual leaders who play the obedience card). Of great consequence to those who are exhorted is that obedience to commandments to the extent that small details in ones’ life are regulated produces a 4th stage person in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. Conditioning for social order (often invoking the specter of destructive anarchy when order breaks down) produces (perhaps justifiably) a majority of a given population in this country who believe following laws is a must and who are unconcerned (in a liberal democracy, for crying out loud) whether the laws are legitimate. The 4th Stage is the legitimate adult stage, but still a relatively low level of moral development, a stage containing the majority who, perhaps without thought, have assigned their agency to a series of “others” who reiterate or promulgate the rules.

The idea that a majority of a given population needs to be quietistic (and even to some degree fatalistic) in order for some minimum social order to be maintained has merit. If an entire population actively pursues free agency it is very likely that chaos will result. However, the same reasoning would suggest that society have enough tolerance and “give” in its system for some proportion of its citizenry (unselected, but allowed to function) to interpret rules fairly freely in order to bring a necessary dynamic and progressive element into the community. Rigid rules freeze a community in its tracks and leads to either the death of, or severe limitations on, the creativity of its citizens.

The outcome of that is observable all over the world as hundreds of cultures took this general route hundreds of years ago and settled into comfortable patterns that persist to this day, creating cultures in which its members feel comfortable but in which there are strong yearnings for the developments of a dynamic society which of necessity allows maverick creativity.

It would seem that the goal of the Gospel of Jesus Christ should be to create an environment in which individuals have the encouragement and the tools to develop as Autonomous Moral Agents (of Kohlberg’s 5th Stage) who think for themselves, make more decisions based on what is right—rather than what self-interested individuals claim to be right--and defy the faulty morality of groups. Groups, experience shows, inevitably regress to a self-serving morality that pays little attention to what is right, giving way, instead, to what maintains the status quo and which maintains or strengthens the group. The 5th Stage requires that individuals sufficiently inform themselves that they are armed with the information needed to make good moral decisions, develop the reasoning ability to use the information and the wisdom of experience (which they should take pains to acquire) to make informed decisions, and be willing to make the decisions called for in given situations without the undue influence of commandments, directives, or peer pressure. Further, of course, they need to be willing to stand responsible for the consequences of those decisions.

It is easily observed, however, that rules can, for convenience sake, be violated and their violation justified by almost anybody, even those who proclaim the sanctity and absoluteness of principles and their associated rules.

Often obedience decrees, which could well be the intention of scriptural admonitions, are extended to a more general command of obedience at the expense of individual initiative, thought, and development. As with so many other things, it seems that application of laws or rules tend to be self-serving conveniences. The concept that “those are not laws, they are just guidelines” seems to be pretty widespread and pretty broadly tolerated, despite lip service to the absoluteness of the rules when appropriate. I tend to be an advocate of the position, but I am impatient with people who make one declaration but follow another muse. However, adherents are frequently admonished that the commandments are not negotiable and that the rules are not a buffet from which one may pick and choose.

By the same token, enforcement of rules and laws seems to often hinge on the self-interest of the enforcer.

The conflict between those who would argue against flexibility in rules and those who often see them as “guidelines” is well explained by differing levels of moral development. Some individuals needs the security of inviolable rules as hedges against the uncertainties of life, while others see rules as restrictive of individual thought and enterprise.

A fundamental moral difference between those who need rules to follow and those who are a little more lackadaisical about rules is that those wishing to have a solid set of guiding rules are automatically able to transfer responsibility for consequences of the rule-following to the rule makers, thus potentially avoiding individual responsibility (as well as yielding individual moral autonomy). Those who slide through rules tend to accept the consequences as of their own actions. Morally, accepting consequences for your behavior tends to demonstrate a higher level of moral development than does rule following. Rule followers see as justice the consequences that flow from rules violations, rather than natural consequences of an action.

The social implications of rule following are that rule followers tend to have little sense of discovery or of risk. Rules by their very nature discourage exploration, discovery and risk, charting a specific pathway of behavior and listing consequences for those departing from that pathway. In this paradigm, a dynamic society relies on those who fudge or break rules (creativity and exploration are, by definition, rule breaking activities) in order to retain its creativity, dynamism and capacity for change.

Those who see rules as unduly restrictive, and often irrelevant, also tend to accept a responsibility for being selective in which rules to follow and which to violate. They develop a scale of harm, understanding the principles behind the rule, but recognizing that no rule can account for all the options and therefore must be comprehensive and restrictive. A “walking man” in the “Do Not Walk” signal box at an intersection, for example, cannot differentiate between when cars are coming and when the crosswalk will be vacant, so must be governed by mechanical time signals, rather than traffic. Rational pedestrians, able to assess potential dangers, are often willing to walk against the red hand when there are no cars coming, a reasonable violation of the law.

Certainly, those who choose to accept the concept of loose interpretation of the law (looking at many laws as “guidelines” rather than rigidly observed) must accept (and logically so) an added obligation of care and discernment in selecting which laws/rules ignore at a given time. Such an obligation adds an element to the individual’s self-development program that is missing with those who slavishly follows the rules/laws/commandments, etc. That self-development program should add to the individual’s ability to make valid judgments and help the individual in his/her development toward Godhood. Slavish following of rules does little but promote some social order across society and stunt developmental growth in the individual. Witness those who are accustomed to the following of rules and find it difficult (and are often reluctant) to make individual judgments because of a stunted skill at making such judgments. For one thing, one who accepts the responsibility to make judgments is also much more likely to be a vigorous information gatherer in order that the judgments be valid. This applies to judgments about family, about social decisions, professional judgments, etc.

There is the paradox, also, of a spiritual life that is in sharp conflict with the secular life of a participatory democracy. In the democracy, under the Bill of Rights, individuals make their own way, develop their own skills and talents and generate a dynamic society. Rule breaking is a norm, since creativity is by definition a rule breaking activity. Therefore, as the Catholic Church finds, citizens of the U.S. seem to be an undisciplined lot who don’t follow the rules and who are very difficult to control (and to predict) . The secular life is also one of great competition in which we vie with each other for jobs, for spouses, for places in the social hierarchy, for friends, etc. The spiritual life, on the other hand is, by its nature, noncompetitive and individuals are exhorted to shun competition as unchristian. It is an interesting exercise to watch entrepreneurial Church leaders reconcile the two demands. Yet, many (majorities in most cases) in this country seek to be given rules to follow, and who then insist on others following the rules also (it often masquerades under the umbrella of the sanctity of the “rule of law”) which creates the puzzling question of whether I should follow the spiritual rules given me, in which case I handicap my development as a God-in-training for rule following is a limiting activity, or whether I should slight spiritual rules (placing them in some sort of perspective) and engage in the competitive secular process. It is the latter process that produces learning and development in the individual, characteristics one would think necessary for development as a God. Therefore, in placing rules in perspective, one must recognize the risks involved in apparently rejecting the commands of Church leaders (more likely calling them “counsels”) and taking actions that seem to fit into the fabric of individual development consistent with consideration of others (do no unnecessary harm).

Perhaps it is a part of the Lord’s great plan for us as individuals to have a lay clergy (and the priesthood), taking advantage of men’s natural rejection of introspection to provide leadership (and instruction) that is ambiguous (some differences between what we are taught and what logic suggests to us—“Do this and you will be blessed,” but that doesn’t really tend to work out for most of us). Such ambiguity, when detected by individuals, forces them to think for themselves. Professional religionists are often sufficiently contemplative that ambiguities are reduced by people who spend their full time working on presentation. Lay clergy are more likely to be involved in matters of the moment and put together presentations that may be shallow, but meet the needs at the time. Such messages are likely to be self-serving, hence the emphasis on obedience as a disciplinary device for convenience, and probably a consequent flexibility and changeableness in the message of he specific church. That is often viewed as adapting to the times, but also by others as changing the message to suit the flfow of the times. In the latter case, religions are accused of yielding to the opinions of members rather than hewing to the gospel line that defined their beliefs.

Those who do not think for themselves, my reasoning goes, take refuge in the obedience thing and are not thoughtful enough to identify the ambiguities, or if they do have feelings of guilt that they haven’t been obedient enough.

Complicating the matter is a sort of patent hypocrisy among rule followers which most often occurs when it is convenient, and either readily explainable or ignorable, to break the rules (or to accept a breaking of the rules) in order to achieve a high priority goal, or in an example of perceived righteousness.

Perhaps the greatest public example of acceptance of rule breaking (or blatant violation of principle) appears to be the Bush Administration in clearly seeking (but not receiving) justification for rule breaking big time in advancing the cause of pre-emptive strike. Prohibition of pre-emptive strikes by the United States had been a matter of pride (we will only attack when we are attacked). Until the Administration capitalized on a terrorist-induced fear to justify invasion of Iraq (which, by the way, became a primary focus of U.S. military efforts, draining efforts from Afghanistan, which seemed to be the center and originator of terrorist activity), that is.

This seems to be a common paradox—avid rule followers, who are highly critical or those who may not be, must deal with the conflict between the oratory of rule following, which tends to target opponents, and the reality of rule breaking among icons, which must be dealt with. Perhaps the three biggest examples are George Bush, Rush Limbaugh and (the Fox news guy). George Bush and his followers, a paragon for rule followers, blatantly and repeatedly lied about Weapons of Mass Destruction and other justifications for going to war with Iraq. Rush Limbaugh, very self righteous about those who break the law for any reason, himself was found to have abused prescription drugs (probably for a very good reason, but one which normally does not wash with the intolerant rule follower).

It is unclear how followers of these folks, who admire them for their unambiguous approaches to the problems of life, deal with demonstrations that life is not as clearcut as we would like it to be, and their icons find themselves doing exactly the things they castigate others for doing. Yet, these icons still maintain a following even after their clay feet are exposed.

One puzzling aspect of rule following is the assumption by those who tend to be slavish about rules (the sacredness of law, etc.) that rules are somehow correct. Hence to follow the rule is to take correct action. The idea that most rules are created by fallible men, whether formally or through custom, and are therefore fairly tentative (in force until something demonstrably better is found) does not seem to enter into the equation. The notion is, of course, that rules somehow take on a sacred tone and must be followed. Even the idea that bad laws or rules must be challenged in order to be changed does not seem to enter into the thinking of those who stake their existence on the following of law/rules. Further, of course, it does not seem to occur that rules are very likely to be made from the self-serving perspective of those who make rules and emerging rules and laws may very well be distorted by the self-interest of those who make and enforce them. Beyond that, the idea that some rules, customs, laws, etc., may have outlived their usefulness (much more likely in a rule following culture than in one in which rules are challenged toward change) and may be more harmful than beneficial in their observance.

This is particularly so in the political climate of the 21sst century in which partisan political groups and special interest groups invest a great deal of time and resources in attempting to have laws passed that will benefit them (inevitably to the detriment of someone else).

A compelling and extreme, example of someone who violated the rules (repeatedly and chronically) to the benefit of society was John Hunter (the father of modern surgery). In “The Knife Man: The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery” by Wendy Moore (2005, Broadway Books, pp.341) whose “lax scruples were necessary to his achievements as a surgeon and biologist.” (The Doctor is Way Out,” Review of above book by Mary Roach, The New York Times Book Review, September 11, 2005, pp. 34-35).

“Hunter’s underweight scruples were utterly necessary to his prodigious achievements as a surgeon and a biologist. As with e the eminent body-snatching anatomists Leonardo and Vesalius, a sentimentality about the dignity of the corpse would have precluded any and all discoveries, and medical knowledge would have remained in the dark for several centuries. Likewise, a casual refusal to carry out casual experimentation on his patients would have kept Hunter from making the tremendous medical strides that he made. Before he arrived on the scene, the healing arts had dead-ended at the theories of Hippocrates. These held that disease was the result of an imbalance of ‘humors” and could be remedied by reducing the unwanted surpluses: by bloodletting, enemas and purgatives, all virtually useless and occasionally fatal.” (p. 34)

In this, as in so many other things, if the established norms, or rules, had not been violated, development of surgery and medical solutions would have remained in place. As is often the case, at any moment a substantial number of people, who may be very influential, believe that all that is to be discovered has been discovered and it is advisable to make rules to make procedures predictable and acceptable and to prevent abuses by practitioners.

By definition, the rule follower believes that a rule, convention, or law is morally correct and therefore permissible to follow. An extension of the rule following practice was noted by former president Jimmy Carter (NPR, November 4, 2005) who broke ranks with fundamentalist Christians (he left the Southern Baptist convention) who, believe they have (as individuals) a special relationship with God (to the extent) that their decisions are automatically correct. Thus, there can be neither compromise not discussion on the issues they take in hand.

It should also be noted that some deontologists follow rules for which they have run the tests of experience, or challenged them through reasoning and therefore may be called principled deontologists, rather than lazy or visceral deontologists. In the event of some rules which are incapable of challenge, the reasoned deontologist still tends to develop a mechanism for testing other rules from the same source and adopting the untested rules on the basis of the solidity of the rules which were tested.

One who concedes to be without discretion in the violation of rules and conventions cedes free agency to those who make those rules, or who benefit from the conventions. By extenstion, this suggests that free agency is capable of being delivered to others.

In response to an e-mail question, relevant to the above discussion (and to the one which follows, #2, asking my reaction to a General Authority's statement that church members should avoid criticism of church leaders, even if they have clearly made a mistake (or, presumably, lied, or another etcetera), I gave the following response. Some is included above, but much is not:

Your question about truth vs. cheerleading (or reinforcement communication) is

a prickly one that has dogged me for a lot of years because it does cause a conflict w/ my journalistic background.

I have come to a conclusion that, for a Church membership perennially in its infancy, with many converts and a largely intellectually immature membership, etc., we are a lowest-common-denominator teaching church, or one-size-fits all in our approach to instruction. That fit is for a church population that seeks instruction (as opposed to developing independence) and is not comfortable with alternatives and conflict (which is seems to me is necessary for individual development and the attaining of Godhood). Thus, a seamless, comforting environment is encouraged not only in churches but in other institutions. My guess would be you have

encountered many in your life and work who are content to be instructed in what to do in a given situation, sparing the need for independent thought and initiative.

Virtually all studies show that between 70 and 85% of a given population seek this instruction; hence it is efficient to adopt such a plan for a church membership (a plan into which Elder Oaks' statement fits perfectly). This leaves 15 percent, or so, who have a sense of inquiry and a need to confront and resolve conflicts who 1) are left to their own devices for adapting to conflicts and working through them without benefit of much peer discussion and 2) an assumption by the Lord that this group is capable of doing that, whereas the majority need to be hand-walked

through life and who, thus, need the conflict free environment that avoids the uncertainty that comes from examination of alternative views. This leads, of course, to public and institutional scorn for intellectualism and very strong emphasis on obedience.

This "iron rod" (as in "cling to") approach leads to the earthly promise of general reward in the hereafter, but also conveniently provides for relatively trouble-free earthly church governance. Hence it is an emotionally attractive proposition for most leaders.

The great risk, of course, is that people who think (and tend to act) for themselves may get

themselves completely off track. I (my arrogance shows) tend to place myself in the smaller group and have been willing over the course of my life to take the risk of being bumped off the track by generally making my own decisions, which I hope are consistent with the broader principles of the Gospel and not tied to administrative exigencies such as Elder Oaks' statements. My experience at the Deseret News and at BYU have reaffirmed to me that my leaders, who are exemplary and inspired in many ways are human, subject to frailties. I treasure their

counsel, but tend to keep my individual autonomy in my decisions and actions.

Hence, I am able to attribute to Elder Oaks a motive of administrative convenience, rather than inspired genius in his statement. Of course, I may be wrong, and I am more inclined to note the inconsistencies between words and action for my own personal guidance (rather than public declarations), but it seems to me that the Gospel seeks truth, and glorifies truth and that mature people are able to assimilate inconvenient truths. We are still an immature church under some stress, so paternal instincts kick in with leaders. I understand that and understand that, as far as earthly values go, I am left to a substantial degree on my own and no one assures me that my decisions are appropriate or celestial. I, and people like me, have to make our own decisions in our own way and stay responsible for them, both here and in the hereafter. I venture also, in my arrogance, to think that slavish obedience is one way to winnow out the large mass to get to the "few are chosen" we are promised. Unwittingly, the slavishly obedient, I sometimes think, are self-voting themselves off the island of exaltation.

Anyway, you asked a simple question and I gave you a long answer that may be

pretty stupid. My academic background further tells me it is counterproductive to encourage church members to limit their knowledge, or their range of inquiry so the comfort zones they establish are not threatened by diverse knowledge. How does one gain the perfect knowledge that is a hallmark of Godhood if one spends a lifetime avoiding new knowledge (see following section)?

If we as humans on earth have the possibility of becoming Gods (an assumption following from the reasons we give for requiring earthly righteousness, etc., and based on “As Man is, God once was; as God is, Man may become”), how do we expect to become all-knowing as Gods if we severely limit our exposure to information during this earthly testing period? It is inconceivable to me that development to Godhood is furthered by avoidance of experience and knowledge. Nearly every experience and acquisition of knowledge helps us to understand ourselves and our fellow man in ways it would seem to me to be necessary for the exercise of Godly powers.

Godhood for individuals is a unique concept of the LDS Gospel. So far as I know, no other organized religion talks of the possibility (remote as it might be) of ultimate Godhood for its adherents. Generalized notions of salvation and/or exaltation exist in other religions, thus making those concepts, perhaps, easier to discuss in our own religion because of our general familiarity with, and recognition of public acceptance of, the concepts. However, Godhood is unique, and we may be very uncertain for a variety of reasons about trying to flesh out a structure for the idea that ultimately we may become Gods. Indeed, we tend to trivialize one of the marvelous and unique characteristics of the Gospel by avoiding discussion of it, generally leaving it off the radar of our consciousness.

The author Harold Bloom, I think it was, said that the notion of Godhood in the Church is an extension of the basic American principle of self-reliance and individual progression. This, he suggests, makes the LDS Church an extension of the American dream, and therefore truly an American Church. (In The Mormons, a PBS documentary, 2007. It could have been in an outtake that he said this.)

My concept of the earthly route toward Godhood—borne of both professional and personal observations and experience (both severely limited, of course)—suggests that this earthly life is a period of unique testing. That is, we will not have our vulnerable (and powerful) physical bodies again, so we must do a number of things on this earth (just as certain assignments generally must be completed in our progression through grade school—reading in the first grade, etc.—lest we fall behind and not have a convenient opportunity to catch up later (in the after life, for example). We have no knowledge of what level of learning (both secular and spiritual) we need to achieve by the time we leave this earth life. However, it would seem to me to be a unique and critical element of our stewardship. If we are not to have the temptations of the flesh to divert us in the various hereafters, we must accomplish on earth those tasks which are unique to the earthly experience. Among those is the development of intellect while contending with the demands of the flesh.

For one thing, conditions are not right in the afterlife to absorb and learn in detail, as well as understand and adjust to, the contrasting and competing social environments in which people function as they try to assert control over their physical appetites while at the same time developing themselves in a competitive environment, seeking individual advantages, developing altruistic motives, becoming driving selfish machines, etc. All this while striving to control their own physical environments. In other words, the afterlife may conceivably provide many of the same conflicts, but without the complicating factor of physical bodies and appetites (and that is a massive complication).

We may not often receive twin injunctions perhaps necessary as Gods in training. What is most often heard is that salvation and exaltation—and presumably progress along the road to Godhood—comes through obedience to the commandments. Also frequently heard, but questionably justifiable, are admonitions to avoid coming in contact with secular information, or even with secular institutions or secularly oriented people.. Many admonitions come by implication (being in, but not of the world is a warning about becoming too worldly—which as a practical matter translates into avoiding over-involvement in worldly matters that would offer experiences and knowledge). Such admonitions seem to be excessively self-protective, designed primarily for weaker souls who do not relish the larger contest entailed in progress toward Godhood.

It must be said that such exposures are risky and that many will fall by the wayside because they could not cope successfully with such exposure. However, it would seem that is also a legitimate part of the plan—face temptation and conquer it (succeed) or succumb to it (and fail) and something is imprinted about you and your chances for Godhood.

Certainly the latter admonition is designed to protect the individual, but what degree of protection is appropriate for an individual interning to become a God? Should that person be shielded, or should the person be required to deal with the daily range of activities that comprise the earth life? Will a shielded person who never confronts temptation be more likely to elevate to Godhood than one who faces temptations, succumbs to some but generally overcomes most? If that is so, the earth life may be largely a wasted exercise.

Indeed, as a Church membership we seem to invoke sanctions on those who appear “too worldly”. Such sanctions have the effect of discouraging learning and of encouraging concentration (or at least give that appearance) on scriptural reading and discussion topics that exclude secular pursuits.

At the same time, it is feasible (though perhaps indefensible) that some avoid learning through a sincere belief that they are not equal to the task of warding off damaging information; and insecurity that protects them but also forecloses them from full knowledge of the world around them they may need to become Gods.

This would seem to be fallacious reasoning, since a basic element of both the Gospel and a democracy is that humans have the ability to make distinctions, and that acceptance of the Gospel helps us to overcome the Natural Man tendencies, which presumably involve being susceptible to temptations of the flesh, among many other things.

However, if one avoids information from the narrow perspective that all that is necessary to know is found in the scriptures (I have had students with that tendency), there would appear to be little excuse for such ignorance.

Certainly not the least of the earthly tests is development of the ability of the spirit (or soul) to control the yearnings of the body for physical satisfaction. Does such control come from avoidance, or from the judicial encountering of temptation and the subsequent effort to understand their power and effect on humans through contact with them to the overcoming of them? It would seem to me the encountering and overcoming of temptation is a much greater achievement than is the avoiding of temptation. Is Godhood likely to come from complete avoidance of situations, or from encountering and mastering these situations? Certainly, one must acknowledge that the encountering of temptation brings the built-in risk of succumbing, but it would also seem that is a natural part of the process and another of the tests along the road to Godhood.

It may be argued, of course, that enough temptations assault us naturally without our having to seek them out in order to see if they can be resisted. There is some truth in that, but when that is used as an excuse to limit normal intellectual development and education, it seems to be an unjustified evasive device rather than a legitimate argument. The willingness of people to avoid learning situations on the grounds they might not be equal to the task, or that they might be too weak to encounter and overcome, is certainly a troubling one that has to do with one’s self image and self confidence, a matter that may be far beyond the reach of spiritual development, but one which cannot be divorced from that development.

Further, of course, is the implicit suggestion that by being obedient I will be imbued with knowledge; suggesting that I may become all knowing merely by being obedient and thereby earning the right to have knowledge provided to me, unbidden, in sufficient quantities, and quality, to fill that particular requirement for Godhood. This, is seems to me is patently absurd, for we are admonished to learn all we can (If anything is praiseworthy, etc. . . . we seek after these things), it appears to me a clear violation of Gospel principles to have wisdom and knowledge bestowed in one area because of behavior in another area. That is, if I assiduously study the scriptures, can I claim to, by virtue of that study, be entitled to become an expert in quantum physics without having the experience of gathering THAT information (with all the experience and insight that entails)? I would not think so. I would think that defies any logic that might be applied.

It is clear this position is not popular with Utah (at least) Church membership because the notion, again implicit, that confining my collection of knowledge to that which comes from scripture study, or from confining my associates to a narrow range of discussants, is sufficient to qualify for Godhood. This appears to be a convenient refuge from learning, which, when teamed with the resisting of temptation may well constitute the most difficult of requirements of this earthly probation.

One reason given for admonishing people to avoid information is the harm it will do. The reasoning is that exposure to harmful material will affect the individual (what you see is what you are) and that harm from such material is inevitable. The best operant analogy is the admonition to avoid gambling lest one becomes addicted to gambling. The fact is that only a small percentage of those who gamble (or of those who drink alcohol) become addicted and that some gambling is not addictive to the vast majority. It is, of course, deplorable that some will be addicted, but it is questionable whether lowest-common-denominator teaching (teaching aimed at protecting the most vulnerable) is useful and progressive for most of those being taught. The general admonition is to never go close to the edge, or to the line, lest you fall off the cliff, or are lured over the line into evil behavior.

Lowest-common-denominator teaching tends to create three classes of people: the first is the vulnerable protected class who need to play it safe in all they do, merely to survive, the second is a crippled vast majority who are talked out of personal development by warnings of the dangers of walking to close to the edge, and who thus play it safe by confining their activities and explorations to the secure when they have the capability to do wondrous things, both for themselves and society if they only were to become a bit adventurous and push some limits, having confidence in their own abilities. The third is the much smaller group who will accept their teachings as advisories and factor those into their decisions, but which will not allow them to have an overwhelmingly decisive role in decisions. This latter group may tend to have greater self-confidence (not necessarily well placed) in their abilities to control themselves, thus reducing the risks inherent in encounters with the forbidden.

The writings in this section, as with others in this series may be viewed as selfishness, self-justification, rebelliousness, etc., but it is important that it be looked at as a critical exercise in self-development. Much of what individuals do to develop themselves may be viewed as hedonistic (pleasure for self), but it might also be that individuals (thoughtful ones, at least) know best for themselves (when a large volume of information is in) and their own interests. The test, of course, for traditional ethics, is whether the hedonism unnecessarily harms others. If by being selfish, or vigorously competitive (see below) one victimizes others, there is little excuse for the action. If, on the other hand, one hurts only oneself by his/her actions, that person must accept the consequences merely for trying to better the self (a broad admonition from God, and the purpose for our earthly existence?), though considerate of others and avoiding victimizing those who are vulnerable and who have been conditioned merely to survive.

There appears to be a certain arrogance attached to striking out on one’s own, an implicit argument that one knows better than one’s spiritual leaders. This should not be the case, however. Such activities, no matter what the accusations, should be done with humility and with the primary purpose (which can only be found within the individual) of developing oneself (with an eye to Godhood), rather than materially enriching (leading a better life or exercising power over others, or merely leading an undisciplined life and not be responsible to anyone other than oneself) oneself because one can by violating instructions.

Yet, it seems inescapable to me that one must, if one is to achieve Godhood, develop a sense of self-confidence, a strong self image of capable decisions. If one does not have confidence in one’s own abilities to make decisions, how can Godhood result. Temerity is not a characteristic of either God or Christ in scriptural accounts of their actions. How shall we achieve the ability to confidently instruct as Gods when we have avoided the experiences, or have not developed the skills of making decisions (complete with standing responsible for the consequences)? Is it that an original God created a template that is a comprehensive plan for us to follow in all cases? A conservative person will say this is so, that the plan anticipates all options in a given situation and that our responsibility is to learn the formalities of the plan. Another person will suggest that in order for us to know how to respond to conditions created by humans, we need to have experience and empathy that will produce responses unique to the situation, even though we will have been able to predict the situation, and the response.

A part of the mystery is why members of the Church do not engage in more discussions of specific steps along the road to Godhood. Salvation and exaltation are very general, and even ambiguous, but Godhood, through the examples of God the Father and of Jesus Christ, has a rich set of precedents and examples to follow.

Curiously, though the prospect of Godhood should be one of the most glorious possibilities for the human being, it is seldom discussed. Most often discussions center around the achieving of salvation and exaltation. I would suspect that the notion of Godhood seems so far outside the realm of possibility that we tend to look at, emphasize, and discuss those things which we may consider most likely to be reachable, and the salvation/exaltation dichotomy seems much more possible for the human being than does Godhood.

Yet to ignore the prospects of Godhood looks very much like engaging in a self-fulfilling prophecy—if we discuss salvation and exaltation we are likely to be (for the present, at least) satisfied to reach those goals. However, there is still a large question out there about whether merely aiming at and reaching those goals will bring Godhood within a closer shouting distance. Missing in that equation is a very real difference in my mind between seeking salvation and seeking Godhood. That is, when I seek salvation, or exaltation, I probably tend to become fixated on the rules necessary to achieve those goals, which are very short sighted from an eternal perspective. Seeking Godhood, on the other hand has already been discussed as an activity that requires a huge amount of learning and accumulating of knowledge. The analogy is that I am looking at my feet to see what the next step is (toward the goal perceived as achievable) to salvation or exaltation. There are specific requirements (necessary but perhaps not sufficient for Godhood) for salvation and exaltation—baptism, priesthood, family, etc. The requirements for Godhood, on the other hand, are likely to be much more extensive and inclusive. If I am to become a God and need to know everything, I need a far more inclusive attitude toward thought, contemplation and education than I would need in order to fill requirements. My additional analogy has to do with students at BYU, or any university: If you merely fill the requirements for graduation you have little assurance you are an educated person. There is a marvelous education to be had at any university, but the individual student must seek out the resources available for that education in order to achieve it. The university (just as life) doesn’t guarantee an education, merely a filling of requirements in order to receive a degree. A degree is merely a paper that certifies the student has completed the university’s requirements. The education, which comes from a student exposing herself to much that is available, but not required, both academically and non academically does not proceed from a list of requirements. It is a much more abstract creature that one may not know whether or not one has, but which is demonstrated through daily activity and quality of approach to life problems and dilemmas. Similarly, filling paper requirements for salvation and exaltation may not assure Godhood, they only assure that the physical hurdles have been cleared. Godhood is probably achieved by accomplishing those non required things that make the complete person required for Godhood.

Thus, if Godhood were more a part of spiritual discussions, there would be more of an emphasis on the broader learning process and less of the limiting preoccupation with taking the next step.

Of course, it can be argued that the earth life is not sufficient for reaching Godhood, but it appears inescapable that the unique circumstances of the earth life are critical to the making of quantum leaps of progress toward Godhood because observations of characteristics of life on earth are apparently the closest to developing the wisdom that will be needed as a God in coping with other earths.

David Smith had for awhile on his daily e-mail homilies a quote from Seneca to the effect that undesirable ideas that enter our consciousness are far more difficult to rid ourselves of than if we did not have the ideas at all (It is easier to exclude harmful passions than to rule them, and to deny them admittance than to control them after they have been admitted. - Lucius Annaeus Seneca, philosopher and writer (c. 3 BCE - AD 65))

The implication, of course, is that it is better not to tempt our own resolve by allowing these things into our consciousness. I argue that Godhood requires us to not only let some of those things into our minds, but to show the characteristics necessary to assess them and reject them if needed. Such avoidance, it seems to me, is not character building and does not prepare one for the understanding needed for Godhood.

Another interesting aspect of learning, and its encouragement, lies with the administrative structure of my church, or of any other church, I suppose. Once I become a spiritual administrator (bishop, pastor, priest, etc.) with a flock to shepherd, I tend to lose interest in the learning process and my primary priority is the saving of the flock. Hence, we tend to have instruction, rather than discussions. Discussion tends to be discouraged for the confusion diverse views and questions bring to the table. The diverse views raise questions members of my flock may not have thought of and may become troubling to them, sowing seeds of doubt. Questions are most likely to be answered by speculation, in the absence of specific information, also sowing seeds of doubt. Seeds of doubt, which in an educational setting among mature individuals is viewed as healthy for the intellectual stimulation and critical thinking that develops the thought processes and makes a more well-rounded and autonomous individual, is not healthy in groups of immature individuals and only raises the confusion quotient. Seeds of doubt all too often result in a falling away, which an administrator seeks to avoid at all costs.

Saturday, May 31, 2008

Friday, May 30, 2008

About That Liberal Bias in the Media

When does a national discussion really begin over conservatives' accusations about the media with responses to the accusing fingers that nail journalists as liberals? The silence by those who should be vigorously arguing the critical merits of a liberal media in a liberal democracy has been deafening. Among those are media people themselves, media ethicists, and a raft of other oughta-be defenders of the media system.

Such a discussion would not be trivial ideological bickering, and defensiveness by journalists, but would only begin to acknowledge the harm of silence in fertilizing the seedbed of a dangerously imminent threat to historic liberal democracy. Lest this become a political battle it should be made clear the discussion would be about conservatives (those who resist change by limiting and ridiculing public dialogue) and liberals (who see change as natural and desirable, pushing for pluralism and vigorous discussion).

The danger is that the United States is demonstrably at the trailhead of a path well worn by countless cultures into a restrictive communal (hence, ultimately conservative) tradition. Those cultures, whatever their origin, comprise nearly three-quarters of the world’s population today. And the United States, arguably the most liberal of democracies, is the world’s greatest hope in resisting global conservatism with its inevitable stagnation and inability to change with conditions.

Accusations against journalists conclude, of course, that media have a liberal bias, with the direct claim that such a bias is somehow harmful to society and at odds with the popular will. Of course journalists are liberal, and that’s the way it should be in a liberal democracy.

The very nature of journalism in a liberal democracy should make that statement self-evident. Yet, journalists fail to defend themselves, passively standing aloof from a national conversation (a one-way conversation, to be sure) that makes it appear that journalism is an ideological pursuit.

The normal journalist, residing somewhere along a scale of liberalism, rightly displays an ideology of pluralism, certainly a liberal characteristic and the touchstone of journalistic endeavor; cover all relevant views. The conservative journalist, however, inevitably, and often proudly, ideologizes the product, with strong end-result feelings in mind, whether it is rallying support for invading Iraq or throwing support behind construction of a new stadium in the community. Thus, the term conservative journalist is, by nature, an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms.

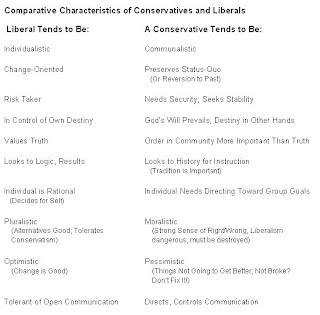

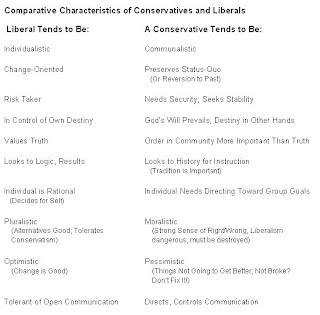

Differences between a liberal and a conservative are easily observable and quickly recognizable for their impact on journalism, for the outlooks on open communication is profound.

A conservative person seeks comfort in the familiar and strives to protect and strengthen the customary, even tending to devalue truth to protect the norm. For examples of this, see the reliance on inviolable tradition in communal cultures, and the growing reliance on tradition, or unexamined dogma in the United States. The first is a stance that militates against risk taking or change, and the second sees protection of the status quo as more important than truth telling. Telltale reversals of form by the Florida and U.S. Supreme Courts in the 2000 presidential election are prime examples of this.