Such a discussion would not be trivial ideological bickering, and defensiveness by journalists, but would only begin to acknowledge the harm of silence in fertilizing the seedbed of a dangerously imminent threat to historic liberal democracy. Lest this become a political battle it should be made clear the discussion would be about conservatives (those who resist change by limiting and ridiculing public dialogue) and liberals (who see change as natural and desirable, pushing for pluralism and vigorous discussion).

The danger is that the United States is demonstrably at the trailhead of a path well worn by countless cultures into a restrictive communal (hence, ultimately conservative) tradition. Those cultures, whatever their origin, comprise nearly three-quarters of the world’s population today. And the United States, arguably the most liberal of democracies, is the world’s greatest hope in resisting global conservatism with its inevitable stagnation and inability to change with conditions.

Accusations against journalists conclude, of course, that media have a liberal bias, with the direct claim that such a bias is somehow harmful to society and at odds with the popular will. Of course journalists are liberal, and that’s the way it should be in a liberal democracy.

The very nature of journalism in a liberal democracy should make that statement self-evident. Yet, journalists fail to defend themselves, passively standing aloof from a national conversation (a one-way conversation, to be sure) that makes it appear that journalism is an ideological pursuit.

The normal journalist, residing somewhere along a scale of liberalism, rightly displays an ideology of pluralism, certainly a liberal characteristic and the touchstone of journalistic endeavor; cover all relevant views. The conservative journalist, however, inevitably, and often proudly, ideologizes the product, with strong end-result feelings in mind, whether it is rallying support for invading Iraq or throwing support behind construction of a new stadium in the community. Thus, the term conservative journalist is, by nature, an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms.

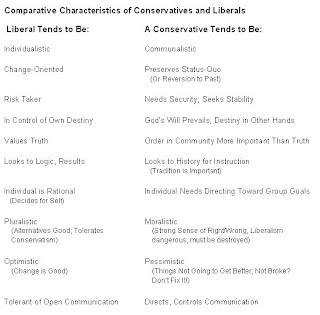

Differences between a liberal and a conservative are easily observable and quickly recognizable for their impact on journalism, for the outlooks on open communication is profound.

A conservative person seeks comfort in the familiar and strives to protect and strengthen the customary, even tending to devalue truth to protect the norm. For examples of this, see the reliance on inviolable tradition

in communal cultures, and the growing reliance on tradition, or unexamined dogma in the United States. The first is a stance that militates against risk taking or change, and the second sees protection of the status quo as more important than truth telling. Telltale reversals of form by the Florida and U.S. Supreme Courts in the 2000 presidential election are prime examples of this.

in communal cultures, and the growing reliance on tradition, or unexamined dogma in the United States. The first is a stance that militates against risk taking or change, and the second sees protection of the status quo as more important than truth telling. Telltale reversals of form by the Florida and U.S. Supreme Courts in the 2000 presidential election are prime examples of this.“Conservative” decisions denote rejection of risk in favor of what is known (familiar); conservative dress, for example, clearly denotes preference for the familiar and accepted. Certainly, conservative behavior is for the most part virtuous, but the common characteristic is that such behavior rejects (and discourages) change, casting votes for retaining the status quo in a society that thrives on change and discovery.

A liberal in the tradition of a liberal democracy, on the other hand, has a rapport with change and differences, certainly a stance that makes risk taking a desired, normal activity. It is public dialogue that makes us captives of change.

Lucian Pye argued a half century ago that developing countries ought to be made “captive of change” if they were to join the world community as independent economic entities. They generally have not achieved that state and are in similar states of development today as 50 years ago.

The journalist learns from early instruction to look for, and report on, what is different. Conservatives often see this reporting as an attack on the status quo and respond with denunciation of the journalist and defense of The Order. The practical effect of news is to present audiences with alternatives to the status quo, anathema to the conservative. Good journalism makes individual change and adaptation to changing conditions possible for audience members.

Conservative journalism, on the other hand, tends to reinforce the status quo by reassuring audiences (whether by omission or commission) that all is well, discouraging dialogue, or warning audiences of threats to the status quo. Such “journalism” is a form of control that removes agency from audience members--a cardinal sin in a liberal democracy that relies on individual rights and assumes the rationality of the human creature.

And control is a primary characteristic of the conservative, seeking to direct social behavior--as in warning of the liberal media agenda. The liberal appears at a disadvantage in this scenario because a typical liberal approach is to identify and present alternatives--including the conservative’s warnings--and assume audiences will decide for themselves. While a liberal may be uncomfortable with conservative criticism, it is often ignored with a shrug that indicates acceptance of a system in which this is expected to occur.

At root is the most disturbing element in the imbalance. The conservative, in order to maintain the status quo must destroy the liberal, hence the vitriol, because widespread presentation of alternatives is always a threat to the social order. The liberal, on the other hand, is ideologically bound to allow the conservative full participation in the system. Such a one-sided state certainly appears to tilt the playing field in the direction of the conservative and erroneous retention of the “traditional values that have made this country great.”

Yet, change (with its natural tendency to put traditional values at risk) is a natural consequence of the robust discussion protected (hence, encouraged?) by the Bill of Rights.

Even a cursory examination discloses that common characteristics of the hundreds of traditional, conservative cultures around the world have in common an inevitable drift toward dogged and blind defense of the status quo, and development of conventions designed to discourage actions that challenge the status quo. Among them, of course, is the closing down of any information system that identifies alternatives. These “comfort level” conventions were adopted hundreds of years ago, freezing these cultures in their tracks, with subsequent generations defending the works of their ancestors.

A main aim of the Fundamentalist Muslim movement is not the conquering of territories, but the destruction of the Western forces of change that appear to threaten tenets of Islam.

The discussion laps over into the communitarian dialogue as journalists who adopt an activist stance in community affairs run the very real risk of joining defenders of the status quo by becoming advocates in their drive to direct outcomes, rather than allow the process (often prolonged) to produce relatively consensual outcomes based on full community discussion.

When they the durability of a liberals minority which continually pushes for change is exhausted, society goes conservative under pressures and common consent resulting from limited alternatives.

The long term problem, of course, is that a liberal democracy may become a conservative democracy (another oxymoron). As conservativism strengthens, change is increasingly impossible; the populace becomes more and more comfortable with the familiar and sources of alternatives dry up. As the status quo is more acceptable it becomes more mandatory so succeeding generations see the possibilities before them and are not constricted by tradition and closed information system.

The dichotomous list below contains comparative characteristics that tend to distinguish the conservative person from the liberal. Most comparisons are self-explanatory, and each characteristic often is supportive or, but also is likely to produce, the others.

Appeared in Media Ethics, 2003, Fall, 2003, pages 8, 31

No comments:

Post a Comment